If, however, we cannot calibrate intuition by appeal to sense perception, then, presuming there are no other calibrating faculties in the offing, it would seem that we cannot calibrate intuition and so we have no good (i.e. independent) reason at all for taking intuition to be reliable. We arrive, then, at an apparently defensible skeptical conclusion about intuition.

Such a conclusion, however is not defensible. … This because we can just as easily argue, as countless skeptics have, that sense perception is itself incapable of independent calibration and so we have no non-epistemically-circular reason to treat its offerings as reliable evidence. The calibration concern is, after all, a completely general one.

[Joel Pust, Intuition as Evidence (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000, 2016), 105-6)]

This is because any attempt to calibrate sense perception must take its corroborating premises only from the deliverances of some other faculty, and in the case envisaged, intuition would be the basis of such a calibration of sense perception. (p. 106)

The problem of epistemic circularity is also deeper than the discussion to this point has revealed. (p. 107)

I do think Reid is right to insist that, in light of our inability to non-circularly justify any basic faculty, some reason needs to be given by those who would rely upon one faculty and yet reject the testimony of others. Absent such a reason, the empiricist’s refusal to accept intuition without independent calibration seems entirely unjustified and epistemically arbitrary. (p. 110)

Therefore, if she is to avoid complete skepticism, and its attendant cognitive suicide, but retain a principled skepticism about intuition, the empiricist must start by trusting all our faculties equally and then show that intuition can still be shown an unreliable source of evidence. (p. 111)

Supposing I have succeeded in showing that the epistemic credentials of intuition are no worse, ultimately, than those of sense perception, it is easy to take my means of showing this as indicating how little can actually be said for sense perception or for any of our basic faculties. My epistemic parity argument, then, might be said not to show why we actually have good reason to treat intuitions as evidence, but merely why we have no good reason to treat sense perception as evidence. (p. 122)

In his dissertation, Joel Pust attempts to show the validity of intuition in its utility in philosophy. Intuition as evidence is no more and no less valid than the use of the senses in gaining knowledge about the world. The alternative is a general epistemic skepticism.

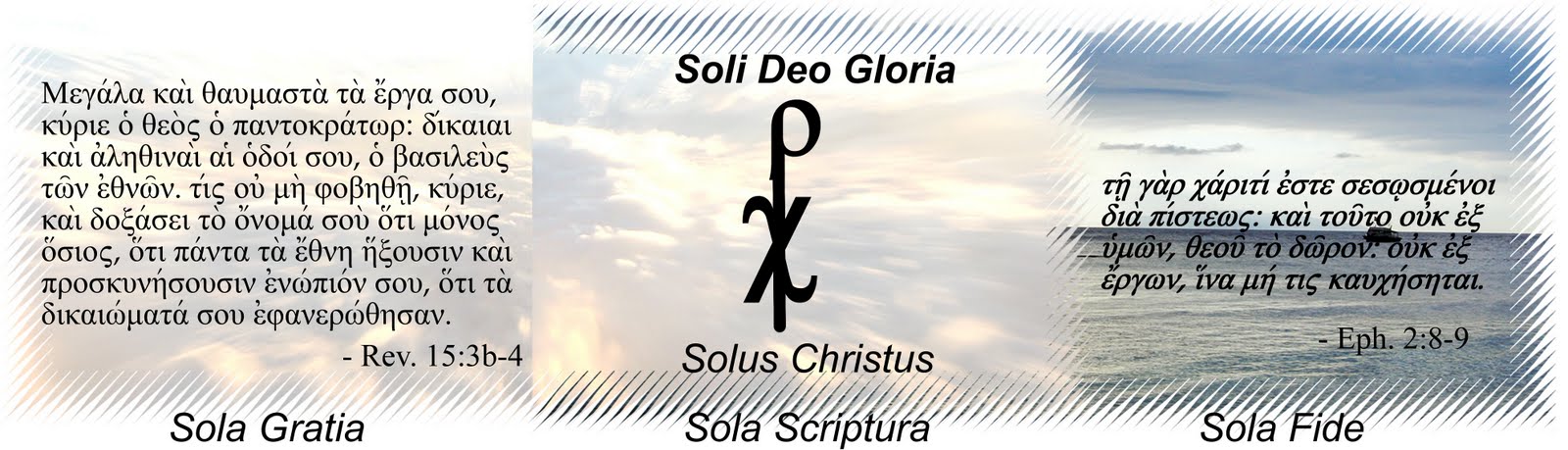

Now, whether Pust has indeed succeeded in making his case can be argued. But in tying the validity of intuition to the senses, I do think Pust is on the right track for sure. Skepticism about intuition seems to merit skepticism in the senses as well. This seems to show, from where I stand, the failure of human philosophy to ever get out of skepticism. It seems to me that revelation from God must undergird all knowledge, for otherwise we are left with general skepticism. Yes, general skepticism cannot be proven, but if all systems fail, then that is what we are left with. General skepticism is therefore not so much proven, but stated in light of the failures of human philosophy.

Intuition therefore, is like the senses. Just as the senses can make sense of the world and yet are fallible and liable to deception, so likewise our intuitions about the world. From a Christian perspective, both derive their general validity from God's general revelation not from themselves, for apart from God's revelation, it is impossible for anyone to know anything of the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment