There is but one only, living, and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions; immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, almighty, most wise, most holy, most free, most absolute; working all things according to the counsel of His own immutable and most righteous will, for His own glory; most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; the rewarder of them that diligently seek Him; and withal, most just, and terrible in His judgments, hating all sin, and who will by no means clear the guilty. (WCF 2.1)

A Reformed confessional view is a view that is stated in the Reformed Confessions. Obviously, since the Reformed Confessions are not Scripture, what they state is not necessarily biblical and true. However, they are the learned judgments of a group of godly men, and therefore, inasmuch as the view is taught in Scripture, it has authority over the life of the believer and the church.

What the Reformed Confessional view is on a topic is one question. Whether the Reformed confessional view (or one of the views) is biblical or not is a separate question, a question reserved for those who are considering subscribing to those Confessions. The question that I want to look at here is not whether the Reformed Confessional view is biblical, but what it teaches and what it does not teaches, using the Westminster Confession of Faith as an exposition of the Reformed Confessional view.

In Westminster Confession of Faith chapter 2 paragraph 1, a condensed sentence was composed expressing the doctrine of God confessed by the Westminster Divines. Of all that is predicated of God, what is pertinent to our discussion is the phrase "without parts," which in two words expresses the entire doctrine of simplicity. God is a God "without parts." But what does that mean? In David Dickson's commentary of the WCF, we are not exactly told what "without parts" mean, except to say that the reason why this is so is because "God is like to no bodily thing, nor can he be represented by any image of corporeal likeness" [David Dickson, Truth's Victory over Error (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 2007), p. 19]. Whatever the phrase "without parts" mean, it protects God's transcendence over the creature.

Reformed theologians have of course aided us in our understanding of the phrase "without parts." Herman Bavinck succinctly states that "simplicity is the antonym of 'compounded,'" and "if God is composed of parts, ... then his perfection, oneness, independence, and immutability cannot be maintained." (Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, 2.176). Francis Turretin states that simplicity means that the divine nature is not only "free from all composition and division, but also as incapable of composition and divisibility" (Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, 3.7.3). A more recent systematic theology merely states that God is "one and indivisible, not composite" (Robert Letham, Systematic Theology, 157), citing James Dolezal's book on the issue. From all that has been seen so far, it seems that the doctrine of simplicity requires an a priori commitment to some form of Aristotelian mereology, or does it?

It is indisputable that the Reformed confessional view on simplicity emerged in an Aristotelian context. But the question remains as to what the doctrine was meant to be teach. One can either go the route of asserting that the Westminster Divines intended to teach Aristotelian metaphysics, as some have obviously done, or one can state that they are trying to teach biblical truths using the existing prevailing philosophy of their time, Aristotelianism, as a tool. If one takes the former tool, one can either agree with the confessions and assert that they are biblical, or reject the confession as being unbiblical. The three options of dealing with the Reformed Confessional view on simplicity are as follows:

- Reformed Confessional view is Aristotelian, it is unbiblical and to be rejected

- Reformed Confessional view is Aristotelian, it is biblical and to be embraced

- Reformed Confessional view uses Aristotelianism as a tool. It is biblical, but the tool is not essential

There are many today who seems to think we have only options 1 and 2 to choose from. Many who claim to be all about the retrieval of Trinitarian orthodoxy (like James Dolezal) have taken position 2, where Aristotelian metaphysics as mediated by Thomas Aquinas is a prerequisite for Trinitarian orthodoxy. The claim is made that rejecting Aristotle and Aquinas would imply the rejection of the Reformed Confessional doctrine of God (Option 1). However, why are we only discussing options 1 and 2 as if another option is not available for us?

The relation of theology and philosophy is a fraught one throughout the history of the church. In her better times, philosophy is to function subservient to theology, as the handmaiden to theology. In other words, theology uses philosophy in its thought, but it itself beholden to no one philosophy either ancient or modern Philosophy is to be a tool to theology, meaning that if the tool outlives its usefulness, it is to be discarded for another tool. Since God is the God of Creation, He necessarily transcends human thought, and therefore we cannot claim that any one philosophy is fully adequate to address all questions concerning God.

This basic principle (an epistemic application of finitum non capax infiniti) means that option 3 is a more viable interpretation of the Reformed Confessional view of simplicity. We have noted that David Dickson, though commenting on the WCF around that time, did not go into depth into what simplicity means. We note that WCF 1.9-10 teaches the supreme authority of Scripture over all matters of faith. It seems clear that the Divines held philosophy to be a handmaiden to theology, and therefore, they would see Aristotelianism more as a tool than as a system that we must necessarily hold on to. Also, from the doctrine of perspicuity of Scripture, it seems clear that, whatever simplicity means, it must be simple enough to be expressed without philosophical language if it is indeed biblical.

What is the main point about simplicity? Perhaps the question can be asked: What happens if we say that God is not simple? According to theologians, a God that is not simple is made up of parts or divisible into parts. In other words, such a god could be created by combining various substances or attributes together. Or such a god could be divided into lesser "god components." What does that mean in simple terms? A non-simple god can be formed by putting divine parts together like creating a Lego set. Or a non-simple god can have a part removed (e.g. his wrath), and he would still remain "God." A slightly deficient god to be sure, but a "God" nonetheless.

Phrased this way, is there a way to understand simplicity without Aristotelianism? Yes. The core of simplicity is simply this: God cannot be any other from what He Himself is. It is the whole God, or nothing. One gets God, "warts and all," except of course God has no warts.

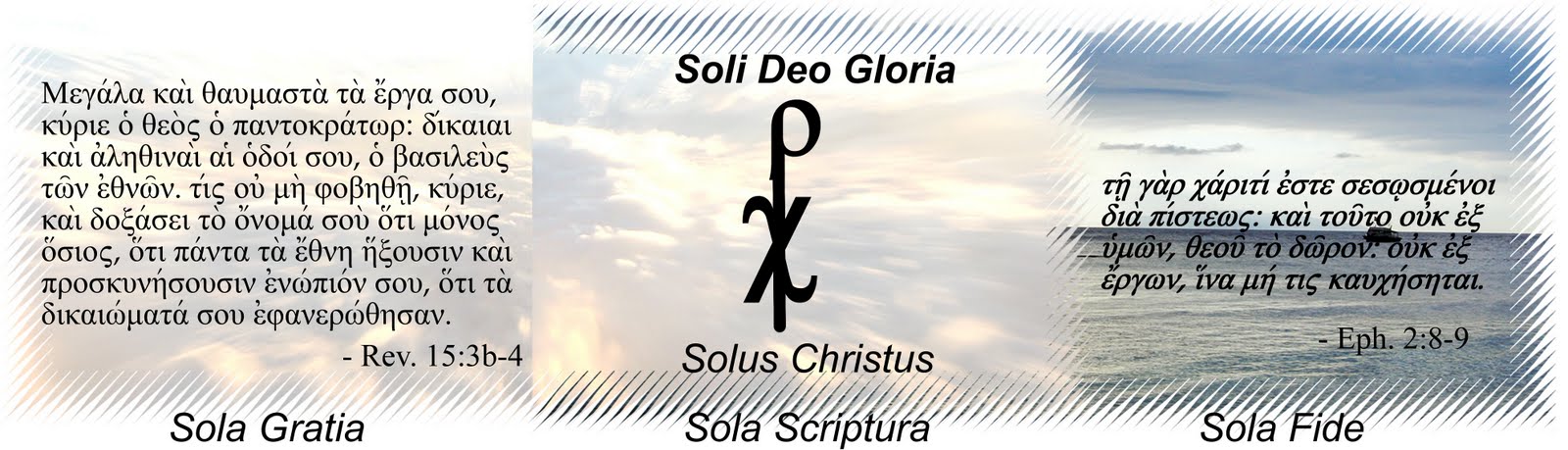

The Reformed Confessional view on DDS, as more consistently interpreted along the lines of option 3, is the view that God must be taken whole, or none. In line with the Reformed tradition of Sola Scriptura and scientia sub Scriptura, this sems to me to be the most consistent Reformed view on the topic of DDS. One is free to explicate how that works using different philosophies including Aristotelianism, but one is not free to mandate that only one philosophical interpretation of DDS is THE Reformed view on the topic.

2 comments:

That was very helpful. Thank you!

Hi David,

Thanks

Post a Comment