If you can predicate what-ness of light (quiddity), and you must or you couldn’t speak of it properly at all, then it has being. Quiddity = essence perceived through a thing’s “to be.”

— Josh Sommer (@1689Broadcast) March 25, 2022

You can’t measure a thing that has no ontology. Geeze. You are predicating a “to be” is a thing, then denying it has an ontology. And in doing this, you’re denying the law of contradiction. I can’t continue the conversation if such is maintained.

— Josh Sommer (@1689Broadcast) March 25, 2022

I have been busy with work and other stuff in real life, so unfortunately I cannot read and write as much as I would like to. I still get involved in Twitter discussions though, so this recent exchange has been helpful in illustrating one main issue of contention I have with classical theism.

Classical Theism, being formed in the Middle Ages and mostly complete by the high Middle Ages in the time of Thomas Aquinas, assumes a realist ontology. Everything that exist has real existence. A thing is made up of a substance and its accidents. Aristotelians focus on the fourfold causation that underlie each thing, and all things are explained by Aristotelian causation. As long as something exists, it must have a cause—material, formal, efficient and/or final.

Such an embrace of Aristotelian ontology commits the Classical Theist to assume that everything that is a thing must have real existence and be explanable by the four causes. But the problem arises as to whether all things have real existence at all. Just because something is a "thing," a noun, does not necessarrily mean that it has real existence. Now, here we are not talking about things like unicorns, which do not exist in this world but can be conceived to exist in a possible world. Rather, we are talking about things that exist in this world, but I would assert they do not have real existence at all.

In my interaction with Joshua Sommer, I had listed three things: Light, Gravity, and Color. But for the purpose of this post, I would like to look at a slightly more expanded list of Shadow, Light, Color and Gravity. It is my assertion that these things are examples of things that exist and yet do not have real (or ontological) existence. They are actual phenomena, but not things that have real ontological existence. These function as counter-examples to the idea that all things can be explained by Aristotelian causation, and each must have essences of their own.

What is a shadow? In physics, a "shadow" is an artifact formed when light to an object is blocked by another object. A "shadow" is not a thing as it has no mass or substance, energy or form. A "shadow" is an area where there is absence of light where the obstruction has cut off the light. During a solar eclipse, the moon moved across the day sky casting a shadow upon the surface of the earth, which we perceive as a solar eclipse when the day dimmed to twilight for a few moments during a full solar eclipse.

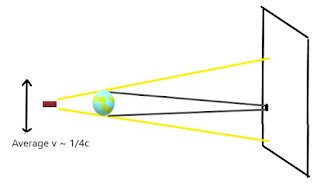

An interesting fact about shadows is that they can "move" faster than the speed of light. In a thought experiment, a huge screen with a height of a few light years is placed about 10 AU away from the earth. A cosmic laser flashlight is put in the place of the sun and shone upon the earth. The flashlight oscillates vertically 1 AU up and 1 AU down, with an average move speed of a quarter of the speed of light (c), as follows:

In this figure, the shadow of the earth will oscillate down and up as the torchlight oscillates up and down. This shadow will be moving up and down the screen faster than the speed of light, since the earth is closer to the rapidly moving torchlight than the screen. But we know that nothing can go faster than the speed of light, so how is that possible? It is possible because shadows are not real things. Shadows emerge from the relation of light source to obstruction of light. They are "real" in the sense that they exist, but they are not real in the sense that they have no essence or form. When a shadow moves "faster than light," what is physically moving is not the shadow but the light from the cosmic flashlight, which travels at the speed of light.

It can be argued that shadows are artifacts, so of course they have no essence. Well, let us look at the case of light. Light is a thing that everyone who is not blind can perceive. But what exactly is light? For some time, light was considered a wave, which was easily to understand until we discovered that light does not need a medium to propagate, which poses a problem for a traditonal understanding of waves. The wave-particle duality of light, with the discovery of the photon through the photo-electric effect, complicates matters even more. While hard to understand, scientists however have the relative luxury of ignoring how their findings affect our understanding of ontology. Philosphers and theologians do not have that luxury. So how do Aristotelians deal with the issue of light? That is a very good question.

The main problem with light and photons is that light is not matter; photons have no mass (effective mass through using Einstein's famous equation is not the same as actual mass). Photons are also transient particles, since they are present only when light is shining, unlike protons and neutrons that are always present as matter. How can something that has no matter has an essence? Light has no form either, and one does not even directly measure light. Light is measured by the amount of illumination (or energy) it gives, which is to say the amount of light is a measurement of its effect not the thing itself. Measuring luminosity involves taking in light, and the amount of light taken cannot be measured and then put back into the system, but rather the light is "used up" as its effect is measured.

Color is another interesting phenomenon. In modern physics, we understand that color is what our minds perceive through receiving light waves into our eyes that have the wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. In other words, color is subjective, as it requires a subject to perceive it. Color is still universally recognized in the sense that all men will see grass under the light of the sun to be greeen. However, it is universal not because it is an objective truth but because all human eyes work that way. Since it is perceived by the brain, it is always possible that an animal with a differently wired brain and eye will perceive different colors differently. Red might be invisible, blue might be greenish, and Ultra-Violet seen as blue to such an animal. Our actual perception of color will be different from that animal's perception, and who gets to determine which color is the "true" color of the grass under the light of the Sun?

Color as such is an emergent property at best. Unlike shadow or light, it also subjective. Therefore, it has no form and no essence, for there is no such thing as an objective property of "whiteness," "greenness" or that of any other color, for "whitenesss" for one creature may be "orangeness" for another creature. Yet, we have an objective idea of what these colors are, even though they are not objective, which shows that one does not have to have form or substance to conceptually exist.

Lastly, we look at gravity. Ever since Isaac Newton discovered his laws on gravity, we knew that gravity is proportional to mass but not why that is the case. With Einstein's contribution, we now know that gravity is merely the curvature of curved space-time, and the curvature is caused by the mass of the object. This new understanding of gravity however puts gravity in the same category as "Shadow," as something that is an artifact of something else. In the case of gravity, gravity is an artifact of curved space time. Since space time is curved, an object in order to preserve its space-time trajectory must curve towards the object distorting space time.

Recently, there has been an interesting discovery of something matching the hypothetical gravity waves by LIGO. However, such a discovery has no bearing on our perceptions of gravity since the gravity waves could very likely be a shock wave transmitted through the space-time fabric of the universe. From all these, we can clearly state that gravity has no essence and no form. As with "shadow," they exist as real physical phenomenon, but they don't have the essence and form Aristotelian essences require.

In conclusion, I believe I have shown four physical phenomena that actually occur, yet have no form and no essence. The fact is that actual occurence makes no difference as to whether something exists ontologically, which is to say it would have a real essence. Modern physics have shattered the naive ontological realism of Aristotle, and as it fails, so too should we be critical of classical theism with its many unspoken philosophical assumptions.

No comments:

Post a Comment