The position of radical discontinuity in evangelicalism in the 1730s cannot be historically confirmed and is theologically dangerous, for it leaves us with the impression that Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley are the fathers of evangelicalism. The result of this controversial position is that Wesley’s Arminianism could then no longer be viewed as aberrational theology within a solidly Reformed movement. Instead, Reformed and Arminian theology would be given equal status in the origins of evangelicalism, as is often done today. [Joel R. Beeke, “Evangelicalism and the Dutch Further Reformation,” in Michael A.G. Haykin and Kenneth J. Stewart, eds., The Advent of Evangelicalism: Exploring Historical Continuities (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2008), 168]

In closing, I wish to step out of the realm of history by commenting briefly on the consequences of this possibility for evangelical self-understanding. If we think that evangelicalism began in the 1730s, then Wesley and Edwards become its most important fathers. This means that evangelicalism was from its origin equally divided between Reformed and Arminian theology. Neither could claim to be the mainstream doctrinal position. In this sense it is easy to see how Bebbington’s analysis serves to give a strong foothold to Arminianism within the evangelical movement by making foundational one of its most noted proponents. If, however, we reconsider the origins of evangelicalism and find that it is a Reformational and Puritan phenomenon, then the picture looks very different. (Gary J. Williams, “Enlightenment Epistemology and Eighteenth-Century Evangelical Doctrines of Assurance,” in ibid., 374)

The movement spearheaded by John Wesley, notwithstanding his predilection for antiquity, was undoubtedly novel. The historian cannot dismiss it as an aberration, because it was numerically the largest sector of the evangelical movement in Britain. (David W. Bebbington, “Response,” in ibid., 424)

Despite the theological polarity over free will, there was generally a remarkable degree of mutual respect within the diverse ranks of the evangelicals. They had a sense of belonging to a common movement in which their united proclamation of the new birth transcended doctrinal differences. … Methodists were full participants in the Evangelical Revival. Their contribution ensured that the movement as a whole was in many respects discontinuous with earlier Protestantism as well as in other ways continuous with it. (Bebbington, "Response," in ibid., 425)

Let me mention a few things, therefore, which I put into the categories of non-essentials.

One is the belief in election and predestination. Now I am a Calvinist; I believe in election and predestination; but I would not dream of putting it under the heading of essential. [Martin Lloyd-Jones, What is an Evangelical? (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1992), 87]

Is Evangelicalism Reformed? Or rather, is Evangelicalism the overarching set in which we can fit in the Reformers, the Puritans, and then the heirs of the First and Second Great Awakening? That is a historical question with important implications for believers' self-identity. If one is Reformed, is one necessarily an Evangelical? Are Evangelicals the set that comprises all true Christian believers who believe in the biblical Gospel, as many people seem to think so today?

While I am sure there are others who have investigated this issue, David Bebbington has brought the issue of the origins of Evangelicalism into the modern spotlight in academia, with his 1989 book Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. In this book, Bebbington stated that Evangelicalism has its origins in the 1730s and especially through the prominent leaders of the First Great Awakening: George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley. Evangelicalism (the "Old" version, not the "New Evangelicalism" of the 1950s) can be described as possessing four distinct traits: Conversionism (a focus on the necessity of each person to individually turn to Christ in faith for salvation), Activism (a commitment to participate with God in his saving mission in the world), Biblicism (a devotion to the Bible as the Word of God written for all of faith), and Crucicentrism (a focus on Jesus Christ and the substitutionary atonement of Christ for sins) [David W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London, UK: Unwin Hyman, 1989), 5-17]. In the early 18th century, a new movement came into being that came to be Evangelicalism, a new distinct movement that was not present prior to the 18th century.

It does not take much thought to realize the implications of the Bebbington thesis for Christian self-identification. In the collection of essays edited by Michael Haykin and Kenneth Stewart, contributors Joel Beeke and Gary Williams pointed out the obvious implications concerning how Arminianism is to be perceived if the Bebbington thesis is to be upheld. In his response, Bebbington plainly states that [Wesleyan] Arminianism is indeed part of Evangelicalism, and points out how Evangelical Calvinists and Evangelical Arminians cooperated in Evangelical enterprises and outreaches. That Evangelical Calvinists have historically regarded the Calvinisism/ Arminianism issue as a non-essential issue is further proved by Martin Lloyd-Jones in his book What is an Evangelical?, where Lloyd-Jones equated "Evangelicals" with "believers" and therefore held that Arminian Christians who believe in the Gospel are "Evangelicals" since they are indeed saved. In other words, it seems that the implications of the "controversial position" Joel Beeke detests is indeed what Evangelicals have always held to. (I guess Beeke has to decide whether he wants to identify himself an "Evangelical," since the Bebbington thesis has some merit along that line)

Ideas and theories have practical implications, and are not limited to academia. That it takes some time for ideas in academia to trickle down to the ground is definite. The only "impractical theories" and "abstract castles in the sky" present are those that deal with things that have little if any relation to reality; everything else is practical if one actually thinks about them. Here, the practical implications of the Bebbington thesis concerns not only a believer's self-identification, but also the status of Arminianism. If one identifies as an Evangelical, it is not possible, given the Bebbington thesis, to claim Arminianism as heresy. Rather, Arminianism must be seen as a minor doctrinal error, about as errant as differences in one's views concerning the Millennium.

It is because of this understanding of history, among others, that I do not identify as an "Evangelical," but rather as Reformed. I hold to the Canons of Dordt and therefore am precluded from considering "Evangelical" as a valid self-label, even apart from all other considerations. Perhaps if Bebbington's thesis trickle towards the church then we can get a greater self-understanding among Christians.

2 comments:

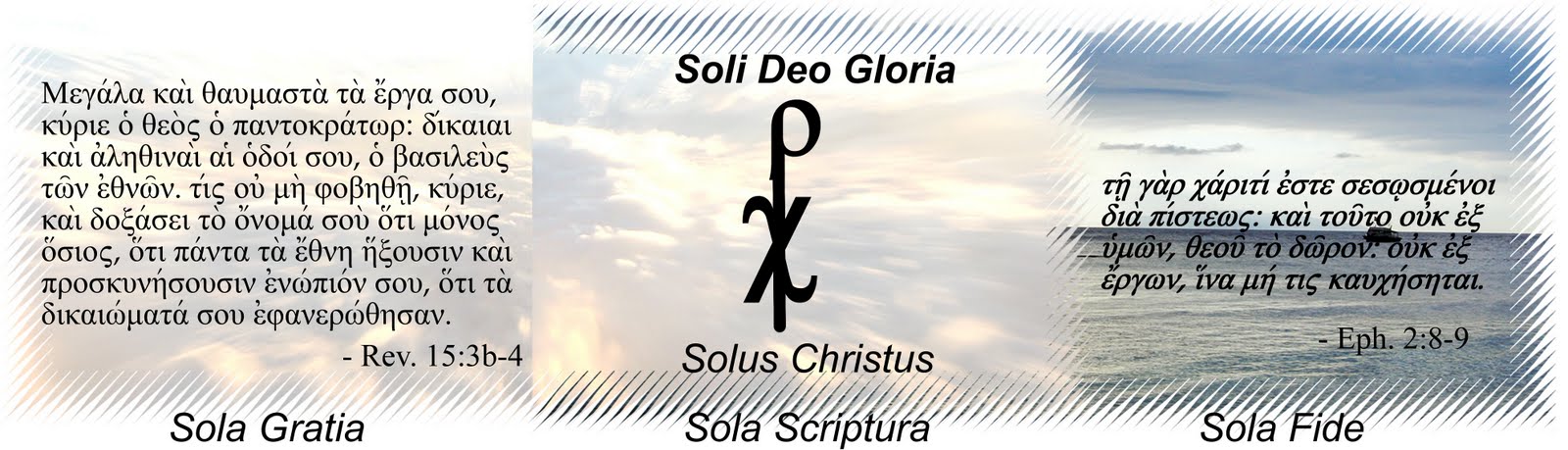

All Calvinists are Protestants but not all Protestants are Calvinists. To be a classical Protestant is to subscribe to the Reformation soli. And that's included in Calvinism. But that falls short of what makes someone Reformed.

Hi Steve,

that's true.

Post a Comment